Transportation on crutches

BEST likes to practice what we preach. We walk, bicycle, and ride the bus. But while on spring break in Florida, executive director Rob Zako hadn’t planned lose the ability to bike, walk, or even stand for another 6 to 12 weeks.

While visiting family and friends in Florida over spring break, I injured my left leg. One moment I was wading into the Atlantic Ocean to go swimming; the next after a wave crashed over me, I could no longer use my left leg.

A visit to the emergency room revealed I had suffered a tibial plateau fracture. I could no longer bike, run, walk, or even simply stand on my left leg without intense pain.

Tibial plateau fractures are serious injuries, and are common in high-impact sports like football, rugby, and basketball. Twisting motions and motor vehicle accidents can also cause a tibial plateau injury.

I returned to Eugene early and underwent surgery by a Slocum Center orthopedic surgeon specializing in trauma fractures. I am expected to make a full recovery—in another 6 to 12 weeks.

But for now, in a leg brace and needing to use crutches, a walker, or a wheelchair to get around, I am temporarily experiencing what for many Americans is daily life: barriers such as slopes, curbs, and stairs to just being able to get around.

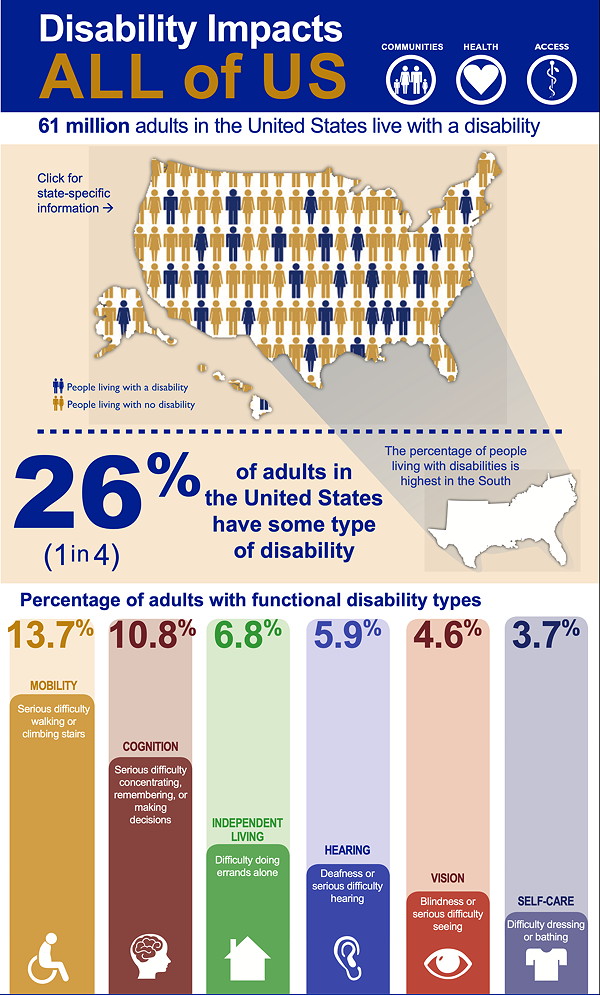

According to the CDC, 1 in 4 adults in America has some kind of disability; 1 in 7 lives with a mobility disability, experiencing serious difficulty while walking or climbing stairs.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law on July 26, 1990, by President George H. W. Bush. The ADA is one of America’s most comprehensive pieces of civil rights legislation that prohibits discrimination and guarantees that people with disabilities have the same opportunities as everyone else to participate in the mainstream of American life—to enjoy employment opportunities, to purchase goods and services, and to participate in State and local government programs and services.

Title II of the ADA prohibits disability discrimination by all public entities regardless of jurisdiction. Public entities must comply with regulations regarding access to all programs and services offered by the entity, including physical access described in the ADA Standards for Accessible Design.

Title II also applies to public transportation provided by public entities through regulations by the U.S. Department of Transportation. It includes the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak), along with all other commuter authorities. This section requires the provision of paratransit services by public entities that provide fixed-route services. ADA also sets minimum requirements for space layout in order to facilitate wheelchair securement on public transport.

Title III of the ADA, prohibits disability discriminated with regards to the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, or accommodations of any place of public accommodation. These include most places of lodging (such as inns and hotels), recreation, transportation, education, and dining, along with stores, care providers, and places of public displays. All new construction must be fully compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines.

But the ADA does not apply to private buildings. In particular, I am discovering that my own home and that of many of my friends’ homes are not ADA accessible. Curbs, steep slopes, and stairs are all barriers to those with mobility disabilities.

Here in Eugene, nonprofits serving those with mobility disabilities include the Lane Independent Living Alliance (LILA) and Mobility International USA.

I feel fortunate that my surgery went well, that I expect to return to an active lifestyle in a few months, and that with so much during the pandemic happening remotely I am able to work from home as I recover.

But my accident has forced me to experience the world, if only temporarily, as others do all the time, and to appreciate the importance of providing mobility options for all, regardless of ability.